Revelstoke-based Yu Sasaki (right) and Chuck (left)

photographing together with Rokuichi Ueki, who shoots from early morning until sunset.

Photo & Caption: Tempei Takeuchi

Ueki Shikaichi strives to establish a freeride culture in Japan while striving to reach new heights as a rider.

He began his riding career at the age of 25, and has been riding with a single-minded focus for the past 10 years, aiming to become a rider who can compete overseas.

Now that he is no longer considered young, he spoke of his experiences and mistakes in the hopes of supporting young, ambitious skiers.

[Profile]

Ueki Shikaichi

Born in Chiba Prefecture in 1985. In search of exciting slopes, he continues to fly around the world, from North America to Japan, New Zealand and Europe, and continues to ski. In recent years, he has become particularly interested in climb and ride, which involves going deep into the mountains. He is passionate about the challenge of tackling bigger slopes. In parallel with his riding activities, he also serves as an organizer of the JAPAN FREERIDE OPEN (JFO) held in Hakuba Cortina, and is responsible for everything from planning to running the event. With the desire to establish the freeride culture he encountered in North America in Japan, he works from Canada to promote the domestic freeride scene.

https://www.instagram.com/shikaichiueki/

Sponsored by: Sweet protection, Hestra, Arva, board butter glide wax, Fintrack north America, Tsubasa Acupuncture and Osteopathic Clinic

Kaichi Ueki, a skier based in Golden, Canada

Golden is a small town in the Canadian interior, just a short drive from the eastern tip of British Columbia, in the province of Alberta. It is here that freeride skier Ueki Kaichi, who skis the mountains of North America, makes his base of operations

Now 37 years old, he moved to Whistler, Canada at the age of 25. He started skiing seriously at the age of 18 and became addicted to park riding, but after moving to Whistler he began competing in big mountain competitions, what we would now call freeride competitions, and continued his activities with the dream of becoming a professional rider who could compete overseas

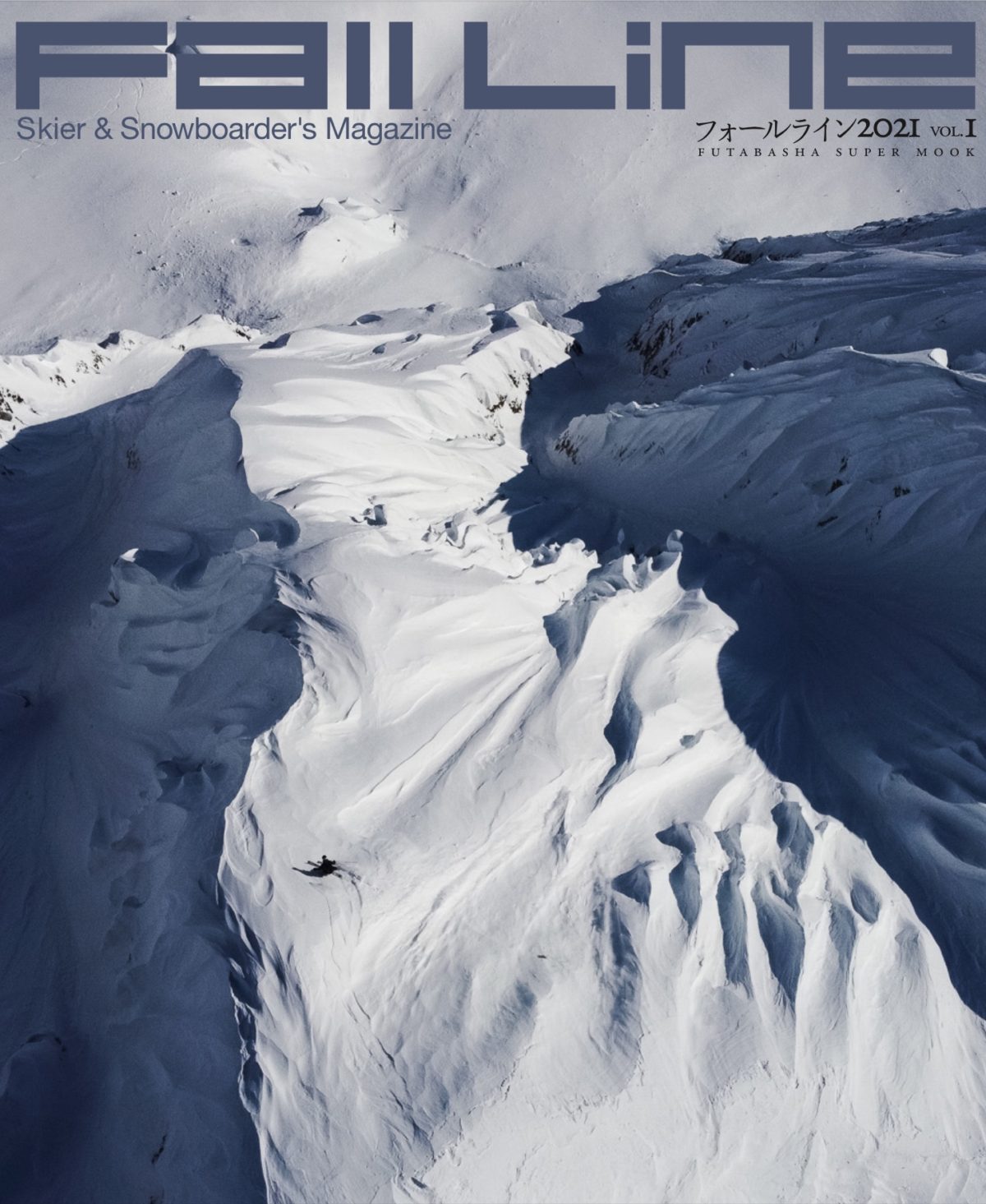

In recent years, he has shifted his focus from competing in freeride competitions to filming, traveling to places like Alaska and the Yukon Territory to record footage and capturing cover shots for Fall Line. He is

also active in a wide range of fields, including co-hosting the JAPAN FREERIDE OPEN (hereafter JFO) held in Hakuba Cortina with his friends. Despite travel restrictions imposed over the past two years due to the COVID-19 pandemic, he has continued to ride, resulting in him being increasingly featured in various media outlets. He has grown and gained a sense of fulfillment by trying new things every year, even as a typical rider.

However, Ueki, who has been working for the past 10 years to reach the level of an international rider, is worried about where he is now. He

is not quite at the level he envisions, whether it be his riding ability, sponsorship situation, or results. Currently, Ueki receives supplies from North American distributors such as Sweet Protection and Aruba, but he has not yet been able to break into their top teams. To secure a contract with a home country in North America or Europe, he needs not only media coverage in Japan, but also exposure in North America and elsewhere.

I'm also feeling the time limit of being 37 years old. Most international riders are around 20 years old. As they get older, only those with a proven track record or who have taken top positions in freeride competitions are active as riders.

Considering my current physical strength, skiing technique, experience, mental state, and the financial resources required for my activities, I believe the next few years are my last chance to stand at the forefront of the field and perform well.

Shikaichi Ueki, who has been active as a freeride skier in North America for over 10 years, said that now, more than ever, he wants to share his journey and the various things he wishes he had done differently with young freeride skiers

If you want to become a professional rider, "Go overseas and start skiing in your teens"

"In the Japanese freeride ski scene, I think most of the so-called professional riders for manufacturers, like me, are under product contracts

The number of people who can make a living as a rider without having another job is even more limited, so if we define a professional rider as someone who makes a living solely from riding, there are probably very few of them

In the current situation, when young riders gain skill and achieve results, there are no rewards or steps in place to compensate them, making it difficult for them to maintain their motivation or move on to the next stage.

Also, when photos of their skating are published in the media, the riders basically don't receive a single yen. The current situation is that there is no system in place to pay riders.

On the other hand, if we look at the riders, for example in North America, the top riders are able to make a decent living. However, by top riders, I mean those who have appeared in top films or achieved results on the Freeride World Tour.

They are the ones who are listed at the top of manufacturers' rider pages. Even in North America, the riders below them all have some kind of other job during the summer. So, in terms of the level of riders who are able to make a living, I don't think there's much difference between Japan and the rest of the world.

So I think that we riders have to aim for that level, and that is surely the level of a professional rider. Juniors aiming to become riders should look at that, go overseas as soon as possible, and ski with high-level riders is the best thing to do. I

think that doing as much as you can in your teens and twenties, and then choosing a path that makes use of that experience from your thirties, will open up a wide range of possibilities for your second life as a skier.

So, when I look back and think about what I was lacking, I realize that I didn't know how to act, so I couldn't take the first step, or while I was busy and working hard every day, I was overwhelmed with the things in front of me and my goals shifted.

In my case, I was injured for a long time, so I spent a lot of time recovering from that. I think it's important to not only improve your skills from a young age, but also to engage in activities that broaden your horizons, have the ability to communicate, and create an environment where you can continue skiing.

I realized this after I turned 30, and since then I've been planning competitions and actively sending my portfolio to manufacturers. For example, I've sent multiple direct messages to the Black Crowes' headquarters' Instagram account, rather than through their domestic distributor, expressing my desire to become a rider. I've

come close, but to be honest, I don't have any notable tournament results or notable video releases, so it's quite difficult for them to take me seriously at my current level.

When I ski with North American skiers, everything is on a different level. They see the line differently, they fly farther off the cliff, and they ski at incredibly fast speeds. I think European skiers have a racing background, but skiers from Canada and New Zealand don't have that, yet for some reason they're good (laughs). I think it's important that they've

been exposed to slopes with fewer restrictions since they were little, and that they ski on those slopes with friends who think like them. I can't make up for that advantage, so even though it's a little late, I'm once again learning from Noriko (Noriko Fukushima) about how to turn and position myself, including how to put my outside foot firmly on my stance."

JFO was born from the desire to spread the skiing experience that I had experienced in Canada to Japan

Immersed in Canadian freeride culture, Ueki started the JAPAN FREERIDE OPEN, commonly known as JFO, in 2017 together with his buddies Jundai Nakashio, Takuma Oike, and Chikara Nakajima. The event

continues alongside the FREERIDE WORLD TOUR (hereafter FWT), which was held in Japan at the same time, and has become a driving force behind the rise of freeride skiing in Japan.

The Ski Open Class is a particularly popular event, with slots filled up within an hour of entries opening.

In Canadian skiing, which Ueki grew up with, both advanced skiers and visitors alike enjoy what is known in Japan as freeriding. It's not just about jumping and flying around, but also about skiing on the best snow when it snows, enjoying groomers first thing in the morning, and tackling tree and steep slopes. They

sometimes even go on adventures in the hike-up zones within ski resorts. 80% of skiers use freeride skis, and such skiing is considered the norm.

Kids who grow up skiing like this inevitably see the slopes differently, and can now ski down any slope with control.

JFO has a junior division, and in addition to competitive competitions, it also holds sessions with top skiers and workshops to learn about avalanches and safety, all with the aim of increasing the number of skiers like this

"What I'm glad about after five years is that when I first started, the participants were mostly in their 30s and 40s, but after we established a junior class in the second year, Tenra (Katsuno Tenran) emerged. Other players such as Daichi (Furuya Daichi) and Kouga (Hoshino Kouga) followed suit, and now the players who came out of the junior class are at the top

Junior athletes are getting better every year, and it's clear to see that they look up to Tenra and the others. I think one of the JFO's goals is to keep that connection going

I don't want the tournament to be just for young people, but it would definitely create a better age balance. I don't think there are many sports where people of all ages can compete on the same terms. And if the young people shine, the older guys' polished aura will also come into play

Since COVID-19, I haven't been able to go to Japan, but being alone in Canada reminds me how important it is to have a place where people who love freeriding can gather. People who normally ski in different places can communicate with each other, get inspired by watching other people's skiing, and it must be an opportunity for all kinds of emotions to intersect."

Ueki said

When the event first began, there was some uncertainty about the direction of JFO. Should it be a competition that would connect athletes to the world, or should it place emphasis on development, or should it be a style that showcases the riding of top riders? While there was no correct answer, one turning point was the FWT, which was held at the same time.

The FWT is based on a globally standardized format, and by accumulating points at each tournament, participants can gradually participate in higher-level competitions.

With the FWT, which has already accumulated know-how for over 20 years, being held in Japan, JFO has become a place where top athletes can shine, but also a place where people with an interest in freeriding can take their first steps, and where regular riders can feel free to show off their skills.

Ueki continues with regards to the future of JFO:

"I would be happy if the junior generation continues to challenge themselves in competitions. I think it would be great if this would deepen the rider pool and make the scene more interesting. It's always young skiers who show us cool, new, genuinely having fun, and new freeride styles

The current freeride scene in Japan is older, but just like other sports, your physical peak is in your 20s. It's not just older guys, but active riders in their 20s who are the ones who are most featured, appearing in the media and leading the scene. I think it's important to have lots of young riders like that emerge

On the other hand, I want to express and communicate the multifaceted and fascinating aspects of freeriding that we know, not just freeriding as a competition or tournament. I don't want to be too biased towards competition. I want to keep the door open at all times

I would really like to increase the number of competitions and incorporate ideas to attract more university ski clubs and junior skiers, but I can't devote 100% to that right now because I also have my own riding activities."

Life in Golden, my base, and the future

When Ueki decided to move from Whistler, Revelstoke was the first place he had his eye on. Home to top skiers such as Sammy Carlson and Yu Sasaki, Revelstoke is a rare ski resort in North America with long, continuous steep slopes. The BC area is dotted with steep slopes and slopes with rich natural topography, including cliffs and pillows, so you'll never get bored

Still, the decision to choose Golden, further east from Revelstoke, was based in part on the advice of Ueki's partner. Another appealing point was that there were several ski resort options from Golden, with many mountains perfect for skiing. Unlike Japan, ski resorts in Canada are far apart. It's rare to be able to drive two hours to reach the next ski resort

Golden, on the other hand, is home to Kicking Horse, the site of the FWT, Lake Louise is about an hour and a half east, and Revelstoke is two hours west. And above all, the snow quality is exceptional. The snow in Revelstoke is known as cold smoke, where the snow lingers like smoke after skiing, rather than settling back on the surface. Golden, where Kicking Horse is located, gets even drier snow

Ueki Shikaichi lives in Golden. He lives in a self-built tiny house that he brought over from Whistler. It sits alone on a large plot of land so large that the neighboring houses are invisible, and he lives in the middle of nowhere, so he is surrounded by nature. In addition to skiing in the winter, he also works as a carpenter in the off-season, and in his spare time he rides his mountain bike, enjoying every moment of his life

When he was in Whistler, he mostly lived among a large Japanese community. When he skated or hung out with others, it was usually with Japanese people, but since coming to Golden, he has started to skate and hang out more with local Canadian buddies. This is another aspect of how his life has changed since he moved

While living this lifestyle, Ueki Rikuichi dreams of becoming an international rider. Currently, he is focusing on his riding activities, so it is difficult for him to find the time, but he hopes to find an opportunity in the future to pass on the experience he has cultivated to the next generation

"I think freeride skiers know what they like and what makes them comfortable. They can feel the joy of playing in nature, truly believe that people live in nature, and feel firsthand that the world is connected to them when they travel with their skis. Being able to have these kinds of feelings is normal among us skiers, but from a society perspective, I think it's surprisingly rare and wonderful

I hope to be able to make time to provide opportunities for the junior generation in Japan to broaden their horizons in skiing, rather than simply skiing down the slopes or experiencing skiing as a sport."